Of Mice and Elephants

Preston L. Allen

The film, DENNIS, demonstrates to an extreme and absurd extent the results of a domineering parent on an adult child. The shrewish mother controls the protagonist Dennis by making him feel guilty and dependent on her when in fact it is she who is dependent on him. She is lonely, it seems, because she has no male companion. Early in the film, Dennis shyly tells her, “I’m going to the movies with Peter.” This is not true. He is actually going on a date with a girl Peter has set him up with, but he must lie rather than tell his mother he is going out with a girl. The lie he tells is shown to us as a fib, a “naughty” little boy’s way of deceiving. You can’t see his hands the way the scene is shot, but you can imagine his fingers crossed as he fibs. His mother responds by saying, “It’s okay for you to stand people up like that.” We can see the result this has on the hulking Dennis now completely immersed in the role of the “little boy” who has disappointed his mom with his “sneaky,” dishonest behavior. To make up for is misdeed, he hangs his head guiltily and volunteers to put away the groceries—one of his “duties” she reminds him. In their cramped tiny kitchen, it’s hard to miss that he towers over her--she looks tiny and frail beneath him. If he doesn’t move out of the way, she cannot pass to go into her room—but move out of the way he does. The contrast in their size in this scene is emphasized by the camera angles, and it is important as the director wants to illustrate that a mother of this type can take away the manhood of even someone as physically imposing as this bodybuilder. And thus the mouse controls the elephant much to our surprise and amazement.

This emasculating due to guilt extends beyond the home as is demonstrated by his awkwardness in social situations in general, but especially around members of the opposite sex. Not only does he shrink before his little mouse of a mother, but he is now exposed to other little mice who can sense his condition and victimize him further. This is illustrated quite effectively in the scenes in the restaurant and at the party. At the restaurant he is a disappointment in the eyes of his date, Patricia, because he drinks Coca Cola rather than alcohol, an adult’s beverage. “I’m in training,” he lies. (It is because his mother scolds him when he drinks we will learn in a later scene.) Also there is a noticeable smirk on his date’s face when he tells another transparent fib when asked if he lives alone. “Yes,” he tells her, averting his eyes. You can see in her face that she doubts his words and is debating whether to call his bluff by asking to go home with this enormous “little child man” for a night of “adult” activities. How amusing that would’ve been.

Instead she invites him to a party and he agrees to go, but first he must take the padlock off his bike—his mode of transportation in a country concerned about the environment? Perhaps. In this film, however, it is just one more framing of him as a child—a giant on a child’s mode of transportation. In the scene at the party, he is made to undress and dance by three more little mice for their amusement. When the “real” adult males appear, they are little mice too compared to him in size, but like all mice they sense his weakness and victimize him as well by laughing derisively at him calling him a “lump.” (Of cheese?) No wonder the giant flees down the stairs and out of the apartment.

Finally, the giant “little boy” cannot take any more of this abuse and returns home. He has tried to escape his mom by running away and it hasn’t worked. The world outside his cage is too dangerous and so he returns to the only place where he feels safe. Now he is so humbled by shame and guilt that he cannot face her, but he must take her scolding if he is to regain her protection. She asks him how the movie was, knowing full well he did not go there. Had he gone there, would his shirt be inside out? She observes too that he has been drinking—he is becoming more like his father, an alcoholic (but perhaps a real man?) She goes to bed, leaving the child thoroughly chastised by her insinuations. Wracked with guilt, he goes into his bedroom, takes off his shirt, again revealing his massive physique, but after a while we see him in her room where he asks timidly, “Can I sleep with you?” What does he mean by that? No, this is not incest, but much worse. The mouse says, “Yes, you may,” rolls over, and pulls back the sheet. And the elephant climbs in—so much like a mom and her giant “little” boy, lying safe beside her.

A blog for lovers of the printed word (novels, short stories, poems--the Ing so to speak), popular film, politics, and casinos (the Bling).

Monday, May 23, 2016

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Lipshitz 6

Reading T Cooper for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Lipshitz 6

Punk Blood

Jay Marvin

Click Here to Purchase Punk Blood

Breath, Eyes, Memory

Anonymous Rex

Reading Eric Garcia for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Anonymous Rex

Vinegar Hill

Reading A. Manette Ansay for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Vinegar Hill

Nicotine Dreams

Reading Katie Cunningham for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Nicotine Dreams

Junot Diaz

Pulitzer Prize Winner!!!

Click Here to Purchase The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Edwige Danticat

New Year's Reading

Click Here to Purchase Brother I"m Dying

Greed

This Brother Is Scary Good

Sweet Music

One More Chance

The genius Is At It Again/The Rapper CHIEF aka Sherwin Allen

Sandrine's Letter

Check out Sandrine's Letter To Tomorrow. You will like it, I insist.

Sandrine's Link

Cool Sites

- Akashic Books

- All or Nothing (My Other Blog)

- Asili The Journal

- Best Gamblling News Site

- Black Star Review

- Book Remarks

- Booktour.com

- Carolina Wren Press

- Click Here for Some Pretty Good Writing Contests

- Dedra Johnson

- Enrico Theoc

- Felicia Luna Lemus

- Florida Book Review

- Foreword Magazine

- Gambling Is Linked to Suicide

- Gambling Is Not Linked to Suicide

- Gaming Law Review

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Geoffrey Philp's Blog

- Get Chief's CDs on CD Baby

- Getting Past Gambling

- Gonzalo Barr's Blog

- Good Reads

- Hallema's Homepage

- Help With Gambling Addiction

- Jeremy Shipp's Website

- John Dufresne's Blog

- Leonard Nash Homepage

- Links to Seminole Casinos in Florida

- Martha Frankel's Homepage

- Michael A. Gonzales

- Miss Snark/ An Agent Gives Great Publishing Advice

- More Addiction Help

- No Gambling.com

- Pat MacEnulty

- ScrewIowa.com

- St. Louis Rams, The Greatest Show on Turf

- Suicide reference library

- T Cooper

- University of Florida

- Vicki Hendricks

- Walter Jacobs's Blog

- Writers Who Read

- Writing with Celia

All or Nothing

Editorial Reviews of All or Nothing

New York Times--". . . a cartographer of autodegradation . . . Like Dostoyevsky, Allen colorfully evokes the gambling milieu — the chained (mis)fortunes of the players, their vanities and grotesqueries, their quasi-philosophical ruminations on chance. Like Burroughs, he is a dispassionate chronicler of the addict’s daily ritual, neither glorifying nor vilifying the matter at hand."

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

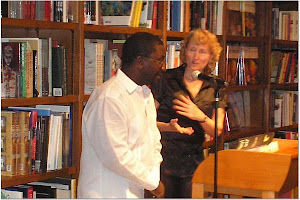

At Books and Books

Me And Vicki at Our Reading

Bio

Preston L. Allen is the recipient of a State of Florida Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature and the Sonja H. Stone Prize in Fiction for his short story collection Churchboys and Other Sinners (Carolina Wren Press 2003). His works have appeared in numerous publications including The Seattle Review, The Crab Orchard Review, Asili, Drum Voices, and Gulfstream Magazine; and he has been anthologized in Here We Are: An Anthology of South Florida Writers, Brown Sugar: A Collection of Erotic Black Fiction, Miami Noir, and the forthcoming Las Vegas Noir. His fourth novel, All Or Nothing, chronicles the life of a small-time gambler who finally hits it big. Preston Allen teaches English and Creative Writing in Miami, Florida.