Last night I saw IRON MAN 2, a very entertaining film that matches up well with the original.

Gary Shandling is great in it--good to see him again. Yours truly is a big fan of the Larry Sanders Show.

Don Cheadle in an action flick? I was not sure that I would like it. He did a fine job, though I did miss Terrence Howard just a little bit. I think Howard and RD, Jr. had better chemistry.

Sam Rockwell--I loved to hate him in Matchstick Men, one of my favorite films, and I loved to hate him in this. He's good as the bad guy.

Scarlett Johannson and Gwyneth Paltrow--fine performances for both of them.

Samuel Jackson as Nick Fury--this was a stretch for me, but Samuel Jackson always brings it. There was not much scripted here for him to work with, but I think he'll do just fine in the eventual Avengers movie.

Mickey Rourke--My god! This guy is amazing as the villain. He sizzles on screen! I love the tooth pick almost as much as the Russian accent.

I kid you not, Mickey Rourke stole the show! Think Heath Ledger--though I do not think he will become the second supervillain to be nomimated for an Oscar. Been there, done that.

Mickey Rourke is gold right now.

Everyone should get on Twitter and vote him on to SNL ASAP.

Thanks,

Preston

A blog for lovers of the printed word (novels, short stories, poems--the Ing so to speak), popular film, politics, and casinos (the Bling).

Saturday, May 22, 2010

Sunday, May 16, 2010

New York Times Book Review of Jesus Boy

The New York Times Book Review.

There is a God. And His blessings are bountiful.

Thanks,

Prof. Allen

__________________________________

The Ecstasy and the Ecstasy

What is it about church that is so damn sexy? The question has bugged me for a long time. An erotic current runs just below the displays of rectitude and purity, despite the hard pews and organ repertory. I suspect it has to do with the congregants’ concerted effort to suppress carnality in favor of distant heavenly rewards. Denying the flesh only makes it throb harder. It’s tricky to defeat one’s own biology, especially when young. It bubbles up during sermons as eyes and thoughts wander. The nape of a boy’s neck sitting two rows up — that modest strip of naked flesh between hairline and suit jacket — can surprisingly arouse.

Sixteen-year-old Elwyn Parker, the protagonist of Preston L. Allen’s novel “Jesus Boy,” is smitten by something just as banal: the glimpse of a twice-pierced, yet unadorned earlobe. The ear belongs to Elaine Morrisohn, 42, a freshly widowed member of his black community’s church, Our Blessed Redeemer Who Walked Upon the Waters. The widow’s earlobes lend credence to rumors that she lived a life of “singular wickedness” before she accepted the Lord. As Elwyn boasts to his high school principal, in this church “we don’t drink, don’t smoke, and our women don’t wear pants.” Jewelry is forbidden, as is coffee, dancing, secular music and most forms of fun.

But these strictures do nothing to repress the congregation’s primal urges, and generations of illicit sex run through this clever and wide-ranging book in which the flesh always triumphs. “Jesus Boy” could well be titled “Jesus People,” for it is crowded with backsliders, hypocrites, horny preachers and shunned “outside” children. All the furtive copulation makes for a general kinkiness that permeates the sanctuary like cheap aftershave. In one case, a couple decides to stop fornicating and get married — only to discover they are distant relatives.

When Elwyn discovers that the girl for whom he’s harbored a long but chaste crush is pregnant, he turns to the pierced widow to explore his own impulses. He visits her just hours after her husband’s burial — she is still in her funeral dress — to ask about the sins she committed in her former life, and whether she ever feels like “yielding.” She does. And she shows him how.

Surely no one does church sexy like Allen. In his worship services, the Holy Ghost descends on women who collapse in the aisle with “spasming legs” and preachers whip their flocks into orgiastic frenzies. The middle-aged widow gazes soulfully at her teenage lover as he strokes the piano during a hymn, “so tight and so fresh and so full of juice,” and calls out an “orgasm shout” that is lost among the holiness shouts.

These people want ecstasy in heaven and on earth. They may lapse into sin, but they can’t shake religion entirely because it is their identity. They quote the Bible — yea, the King James Version — as they beat each other up. They pray before cheating and raise holy hands in the middle of a seduction. One adulterous couple, knowing their congregation will ostracize them if they go public with their liaison, reach an impasse when it comes to finding a new church. As the man ticks off denominations, the woman finds faults with each. She can’t bear to leave her spiritual home of so many years. “Love will conquer all,” her lover finally reassures her. “Love will find a way.”

“Will it?” she responds.

The sinners here take comfort in the notion that “Christ is married to the backslider,” and will forgive their trespasses “seventy times seven” (Matthew 18:22). That’s 490 times, or about one aberration every two months over an 80-year lifespan — not much. Like Ted Haggard-Jim Bakker-Jimmy Swaggart, when their hypocrisy and dirty secrets are revealed, they expect, even demand, forgiveness.

Allen’s writing is by turns solemn and funny. There is a revival scene staged by three ministers — two are African-American, one white — that is hilarious. As the “Rev’run” struts around the stage in a mint-green double-breasted suit berating the audience, the adulterous Rev. McGowan responds with tears, but the white minister leaps to his feet, slings the Rev’run aside and screams gibberish into the microphone before sprinting down the aisle and out the door. The stunned audience “pondered the role of the white minister,” Allen writes, while the two black preachers wondered who he was; neither had invited him. Was the mystery man speaking in tongues, reacting to the Rev’run’s emotional appeal or exhibiting psychosis? The reader must decide if his behavior is any more schizoid than that of the zealous sinners or sinning zealots who people this book.

Allen’s previous books include “All or Nothing,” a novel about gambling addiction (as this one is about religious addiction) and “Churchboys and Other Sinners,” a story collection in which Elwyn is a recurring character. It would be easy for “Jesus Boy” to become fluffy satire, but Allen keeps his characters real. Elwyn, who once aspired to become “a beacon unto the faithful,” becomes something much more profane. His faith wanes, but he still slips into the pews now and again to get his fix by singing the hymns he’s known since boyhood. He leaves before the sermon begins. There is nostalgia for the simple morality, the fellowship, the promise of celestial rewards. Old habits are hard to break.

by Julia Scheeres

There is a God. And His blessings are bountiful.

Thanks,

Prof. Allen

__________________________________

The Ecstasy and the Ecstasy

What is it about church that is so damn sexy? The question has bugged me for a long time. An erotic current runs just below the displays of rectitude and purity, despite the hard pews and organ repertory. I suspect it has to do with the congregants’ concerted effort to suppress carnality in favor of distant heavenly rewards. Denying the flesh only makes it throb harder. It’s tricky to defeat one’s own biology, especially when young. It bubbles up during sermons as eyes and thoughts wander. The nape of a boy’s neck sitting two rows up — that modest strip of naked flesh between hairline and suit jacket — can surprisingly arouse.

Sixteen-year-old Elwyn Parker, the protagonist of Preston L. Allen’s novel “Jesus Boy,” is smitten by something just as banal: the glimpse of a twice-pierced, yet unadorned earlobe. The ear belongs to Elaine Morrisohn, 42, a freshly widowed member of his black community’s church, Our Blessed Redeemer Who Walked Upon the Waters. The widow’s earlobes lend credence to rumors that she lived a life of “singular wickedness” before she accepted the Lord. As Elwyn boasts to his high school principal, in this church “we don’t drink, don’t smoke, and our women don’t wear pants.” Jewelry is forbidden, as is coffee, dancing, secular music and most forms of fun.

But these strictures do nothing to repress the congregation’s primal urges, and generations of illicit sex run through this clever and wide-ranging book in which the flesh always triumphs. “Jesus Boy” could well be titled “Jesus People,” for it is crowded with backsliders, hypocrites, horny preachers and shunned “outside” children. All the furtive copulation makes for a general kinkiness that permeates the sanctuary like cheap aftershave. In one case, a couple decides to stop fornicating and get married — only to discover they are distant relatives.

When Elwyn discovers that the girl for whom he’s harbored a long but chaste crush is pregnant, he turns to the pierced widow to explore his own impulses. He visits her just hours after her husband’s burial — she is still in her funeral dress — to ask about the sins she committed in her former life, and whether she ever feels like “yielding.” She does. And she shows him how.

Surely no one does church sexy like Allen. In his worship services, the Holy Ghost descends on women who collapse in the aisle with “spasming legs” and preachers whip their flocks into orgiastic frenzies. The middle-aged widow gazes soulfully at her teenage lover as he strokes the piano during a hymn, “so tight and so fresh and so full of juice,” and calls out an “orgasm shout” that is lost among the holiness shouts.

These people want ecstasy in heaven and on earth. They may lapse into sin, but they can’t shake religion entirely because it is their identity. They quote the Bible — yea, the King James Version — as they beat each other up. They pray before cheating and raise holy hands in the middle of a seduction. One adulterous couple, knowing their congregation will ostracize them if they go public with their liaison, reach an impasse when it comes to finding a new church. As the man ticks off denominations, the woman finds faults with each. She can’t bear to leave her spiritual home of so many years. “Love will conquer all,” her lover finally reassures her. “Love will find a way.”

“Will it?” she responds.

The sinners here take comfort in the notion that “Christ is married to the backslider,” and will forgive their trespasses “seventy times seven” (Matthew 18:22). That’s 490 times, or about one aberration every two months over an 80-year lifespan — not much. Like Ted Haggard-Jim Bakker-Jimmy Swaggart, when their hypocrisy and dirty secrets are revealed, they expect, even demand, forgiveness.

Allen’s writing is by turns solemn and funny. There is a revival scene staged by three ministers — two are African-American, one white — that is hilarious. As the “Rev’run” struts around the stage in a mint-green double-breasted suit berating the audience, the adulterous Rev. McGowan responds with tears, but the white minister leaps to his feet, slings the Rev’run aside and screams gibberish into the microphone before sprinting down the aisle and out the door. The stunned audience “pondered the role of the white minister,” Allen writes, while the two black preachers wondered who he was; neither had invited him. Was the mystery man speaking in tongues, reacting to the Rev’run’s emotional appeal or exhibiting psychosis? The reader must decide if his behavior is any more schizoid than that of the zealous sinners or sinning zealots who people this book.

Allen’s previous books include “All or Nothing,” a novel about gambling addiction (as this one is about religious addiction) and “Churchboys and Other Sinners,” a story collection in which Elwyn is a recurring character. It would be easy for “Jesus Boy” to become fluffy satire, but Allen keeps his characters real. Elwyn, who once aspired to become “a beacon unto the faithful,” becomes something much more profane. His faith wanes, but he still slips into the pews now and again to get his fix by singing the hymns he’s known since boyhood. He leaves before the sermon begins. There is nostalgia for the simple morality, the fellowship, the promise of celestial rewards. Old habits are hard to break.

by Julia Scheeres

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Lipshitz 6

Reading T Cooper for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Lipshitz 6

Punk Blood

Jay Marvin

Click Here to Purchase Punk Blood

Breath, Eyes, Memory

Anonymous Rex

Reading Eric Garcia for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Anonymous Rex

Vinegar Hill

Reading A. Manette Ansay for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Vinegar Hill

Nicotine Dreams

Reading Katie Cunningham for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Nicotine Dreams

Junot Diaz

Pulitzer Prize Winner!!!

Click Here to Purchase The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Edwige Danticat

New Year's Reading

Click Here to Purchase Brother I"m Dying

Greed

This Brother Is Scary Good

Sweet Music

One More Chance

The genius Is At It Again/The Rapper CHIEF aka Sherwin Allen

Sandrine's Letter

Check out Sandrine's Letter To Tomorrow. You will like it, I insist.

Sandrine's Link

Cool Sites

- Akashic Books

- All or Nothing (My Other Blog)

- Asili The Journal

- Best Gamblling News Site

- Black Star Review

- Book Remarks

- Booktour.com

- Carolina Wren Press

- Click Here for Some Pretty Good Writing Contests

- Dedra Johnson

- Enrico Theoc

- Felicia Luna Lemus

- Florida Book Review

- Foreword Magazine

- Gambling Is Linked to Suicide

- Gambling Is Not Linked to Suicide

- Gaming Law Review

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Geoffrey Philp's Blog

- Get Chief's CDs on CD Baby

- Getting Past Gambling

- Gonzalo Barr's Blog

- Good Reads

- Hallema's Homepage

- Help With Gambling Addiction

- Jeremy Shipp's Website

- John Dufresne's Blog

- Leonard Nash Homepage

- Links to Seminole Casinos in Florida

- Martha Frankel's Homepage

- Michael A. Gonzales

- Miss Snark/ An Agent Gives Great Publishing Advice

- More Addiction Help

- No Gambling.com

- Pat MacEnulty

- ScrewIowa.com

- St. Louis Rams, The Greatest Show on Turf

- Suicide reference library

- T Cooper

- University of Florida

- Vicki Hendricks

- Walter Jacobs's Blog

- Writers Who Read

- Writing with Celia

All or Nothing

Editorial Reviews of All or Nothing

New York Times--". . . a cartographer of autodegradation . . . Like Dostoyevsky, Allen colorfully evokes the gambling milieu — the chained (mis)fortunes of the players, their vanities and grotesqueries, their quasi-philosophical ruminations on chance. Like Burroughs, he is a dispassionate chronicler of the addict’s daily ritual, neither glorifying nor vilifying the matter at hand."

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

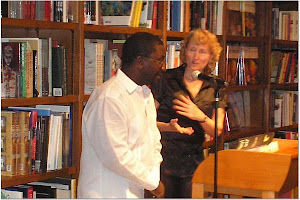

At Books and Books

Me And Vicki at Our Reading

Bio

Preston L. Allen is the recipient of a State of Florida Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature and the Sonja H. Stone Prize in Fiction for his short story collection Churchboys and Other Sinners (Carolina Wren Press 2003). His works have appeared in numerous publications including The Seattle Review, The Crab Orchard Review, Asili, Drum Voices, and Gulfstream Magazine; and he has been anthologized in Here We Are: An Anthology of South Florida Writers, Brown Sugar: A Collection of Erotic Black Fiction, Miami Noir, and the forthcoming Las Vegas Noir. His fourth novel, All Or Nothing, chronicles the life of a small-time gambler who finally hits it big. Preston Allen teaches English and Creative Writing in Miami, Florida.