You can find this report on Candy Spelling all over the internet. I found it at http://www.usmagazine.com/candy-spelling-wins-180000-at-slot-machine.

______________________________

Candy Spelling won $180,000 at a slot machine at the Bellagio Hotel in Las Vegas, TMZ.com reports.

Spelling – mother to pregnant 90210 star Tori – has an estimated worth of $600 million.

She was playing the high-limit slots (maximum bet: $1,000) when she scored the jackpot.

This is Spelling's second large Vegas win. A year ago, she won $200,000 at the Bellagio slots.

______________________________________

So Candy Spelling wins big? Yeah, right.

Let's put this thing into perspective before you go running out to your casino and start banging those one-armed bandits at $1000 a pop. You should gambler as conservatively as Candy did.

Pick your level:

1) Candy Spelling is worth 600 million dollars (nice!), and she won $180,000 at $1000 a pop.

2) You are worth 60 million dollars (wouldn't that be nice), and you win $18,000 at $100 a pop.

3) You are worth 6 million dollars (we wish), and you win $1,800 at $10 a pop. (Oh, this extra 1800 is really going to change my life.)

4) You are worth $600,000 (a few of us), and you win $180 at $1.00 a pop. (Ohhh, how exciting--now I can fill up the gas tank 3 times without have to touch my six hundred thou.)

5) You are worth $60,000 (some of us), and you win $18 at .10 cents a pop. (Ohhh, I'm rich, I got $18 to add to my 60 grand!)

6) You are worth $6000 (many of us), and you win $1.80 at .01 cent a pop. (Ohh baby, I'm on fire now--this machine is hot!)

7) You are worth $600 (too many of us), and you win .18 cents at .001 cents a pop. (Ohh, it's life changing.)

See? The payoff sucks. It almost always does in a casino. $180,000 is not going to change Candy's life anymore than $1.80 is going to change yours if you are at level 6, with six grand in the bank betting it a tenth of a penny at a time.

She did not win a thing, relatively speaking. Her payoff was a mere 180 to 1. If she had played a state-run Cash-3 and hit 3 numbers, her payoff would have been 500 to 1.

Thus, had she put a grand on a winning Cash-3 number (as she dared to wager on each push of the slot machine), Candy would have won a cool half million.

Furthermore, her odds of winning are better in a Cash-3: a reasonable one in a thousand. I'm sure her slots odds are closer to one in a million, or something like that.

So why does Candy Spelling play the slots?

It's not going to make her rich--the payoff of 180 to one is too low and she's already super rich anyhow.

It's not going to break her--the per play is too low--a thousand dollars to her is like a penny to us if we have $6000 in the bank. She could spend a hundred thousand a day (one hundred pushes) every day of the year (36 million a year), and it would still take about 8 years before she went through close to half of her fortune (280 million).

--[That's like one of us regular mortals spending a hundred pennies every day (one dollar--$365 a year), which is a rather mild habit for a gambler--it's not even worth the trip to the casino].

So back to the question. Why does Candy play the slots? She plays it because she is a gambler--if she is a gmabler, then she needs the excitement. She plays it because she has to play--she plays it for the thrill. It is what gamblers seek. The rush. They play. They play. They have to play. They play like children on a very expensive playground. Fortunately, Candy can afford the ride.

Now, if they present her with a slot that costs $100,000 a push, it would get interesting.

Candy would now be playing in the sadistic playground that the rest of us degenrates play in.

Let's do the numbers.

Pick your level:

1) Candy Spelling is worth 600 million dollars, and she bets $100,000 a pop--trying to win $18 million (nice).

2) You are worth 60 million dollars, and you bet $10,000 a pop--trying to win $ 1.8 million.

3) You are worth 6 million dollars, and you bet $1000 a pop--trying to win $180,000.

4) You are worth $600,000, and you bet $100 a pop--trying to win $18,000.

5) You are worth $60,000, and you bet $10 a pop--trying to win $1800.

6) You are worth $6000, and you bet $1.00 a pop--trying to win $180.

7) You are worth $600, and you bet .10 cents a pop--trying to win $18 dollars.

Looks innocent, right? Trust me, it is not innocent at all.

Let's use level 6 as our sample because level 6 is what most of us are familiar with and can afford--the dollar machine with a jackpot of $1000 and a back up prize around $250--in this case $180. [That's right, folks. I am betting that Candy did not win a jackpot--she won a back up prize--jackpots rarely pay out at a meager 180-to-1. To the casino industry's credit, the payoff ratio for jackpots is ALWAYS much higher than 180-to-1. The trick is that jackpots don't pay off very often. So candy was probably chasing a jackpot of $1 million, perhaps, and ended up with a back up prize of $180,000.]

So, let's say that you have $6000 in the bank and you spend $100 a day at $1 a push chasing a thousand dollar jackpot and a measly $180 back up prize. That works out to $7,300 a year--say good bye to you 6 grand in the bank.

I know that this souns like a silly example, spending a hundred dollars a day chasing a thousand-dollar prize (and a measly $180 back up prize)--but this is what most of us do.

Or we spend a thousand dollars a day chasing a $10,000 prize, which is exactly the same thing. In a year you would have blow $73,000. Say good bye to your sixty grand. The only hope is that you hit the jackpot a FEW times, and remember that jackpots rarely hit.

In Candy Spelling's case (level 1), using our new model, at a hundred pushes per day (at a hundred grand per push), she would be spending $ten million per day. By the end of the year, she would have spent over $730 million dollars. Say good bye fortune.

And if there were a slot machine that costs $100,00 per push, Candy Spelling would play it. She would have to--because she is a gambler.

If she didn't play it, then she's not a gambler.

Trust me on this.

Preston

A blog for lovers of the printed word (novels, short stories, poems--the Ing so to speak), popular film, politics, and casinos (the Bling).

Wednesday, June 11, 2008

Candy Spelling Wins Big!

Labels:

crime,

gambler,

gamblers anonymous,

gambling,

luck,

quitting gambling

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Lipshitz 6

Reading T Cooper for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Lipshitz 6

Punk Blood

Jay Marvin

Click Here to Purchase Punk Blood

Breath, Eyes, Memory

Anonymous Rex

Reading Eric Garcia for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Anonymous Rex

Vinegar Hill

Reading A. Manette Ansay for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Vinegar Hill

Nicotine Dreams

Reading Katie Cunningham for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Nicotine Dreams

Junot Diaz

Pulitzer Prize Winner!!!

Click Here to Purchase The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Edwige Danticat

New Year's Reading

Click Here to Purchase Brother I"m Dying

Greed

This Brother Is Scary Good

Sweet Music

One More Chance

The genius Is At It Again/The Rapper CHIEF aka Sherwin Allen

Sandrine's Letter

Check out Sandrine's Letter To Tomorrow. You will like it, I insist.

Sandrine's Link

Cool Sites

- Akashic Books

- All or Nothing (My Other Blog)

- Asili The Journal

- Best Gamblling News Site

- Black Star Review

- Book Remarks

- Booktour.com

- Carolina Wren Press

- Click Here for Some Pretty Good Writing Contests

- Dedra Johnson

- Enrico Theoc

- Felicia Luna Lemus

- Florida Book Review

- Foreword Magazine

- Gambling Is Linked to Suicide

- Gambling Is Not Linked to Suicide

- Gaming Law Review

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Geoffrey Philp's Blog

- Get Chief's CDs on CD Baby

- Getting Past Gambling

- Gonzalo Barr's Blog

- Good Reads

- Hallema's Homepage

- Help With Gambling Addiction

- Jeremy Shipp's Website

- John Dufresne's Blog

- Leonard Nash Homepage

- Links to Seminole Casinos in Florida

- Martha Frankel's Homepage

- Michael A. Gonzales

- Miss Snark/ An Agent Gives Great Publishing Advice

- More Addiction Help

- No Gambling.com

- Pat MacEnulty

- ScrewIowa.com

- St. Louis Rams, The Greatest Show on Turf

- Suicide reference library

- T Cooper

- University of Florida

- Vicki Hendricks

- Walter Jacobs's Blog

- Writers Who Read

- Writing with Celia

All or Nothing

Editorial Reviews of All or Nothing

New York Times--". . . a cartographer of autodegradation . . . Like Dostoyevsky, Allen colorfully evokes the gambling milieu — the chained (mis)fortunes of the players, their vanities and grotesqueries, their quasi-philosophical ruminations on chance. Like Burroughs, he is a dispassionate chronicler of the addict’s daily ritual, neither glorifying nor vilifying the matter at hand."

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

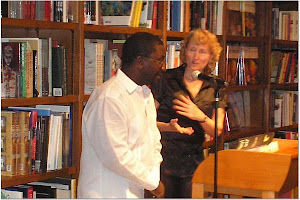

At Books and Books

Me And Vicki at Our Reading

Bio

Preston L. Allen is the recipient of a State of Florida Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature and the Sonja H. Stone Prize in Fiction for his short story collection Churchboys and Other Sinners (Carolina Wren Press 2003). His works have appeared in numerous publications including The Seattle Review, The Crab Orchard Review, Asili, Drum Voices, and Gulfstream Magazine; and he has been anthologized in Here We Are: An Anthology of South Florida Writers, Brown Sugar: A Collection of Erotic Black Fiction, Miami Noir, and the forthcoming Las Vegas Noir. His fourth novel, All Or Nothing, chronicles the life of a small-time gambler who finally hits it big. Preston Allen teaches English and Creative Writing in Miami, Florida.

No comments:

Post a Comment