Here is an article on Bill Bennett and Gambling from an old blog posting (June 2003) on WashingtonMonthly.com.

It's very instructive.

Thanks,

Preston

________________________________________

"We should know that too much of anything, even a good thing, may prove to be our undoing...[We] need ... to set definite boundaries on our appetites."

--The Book of Virtues, by William J. Bennett

No person can be more rightly credited with making morality and personal responsibility an integral part of the political debate than William J. Bennett. For more than 20 years, as a writer, speaker, government official, and political operative, Bennett has been a commanding general in the culture wars. As Ronald Reagan's chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, he was the scourge of academic permissiveness. Later, as Reagan's secretary of education, he excoriated schools and students for failing to set and meet high standards. As drug czar under George H.W. Bush, he applied a get-tough approach to drug use, arguing that individuals have a moral responsibility to own up to their addiction. Upon leaving public office, Bennett wrote The Book of Virtues, a compendium of parables snatched up by millions of parents and teachers across the political spectrum. Bennett's crusading ideals have been adopted by politicians of both parties, and implemented in such programs as character education classes in public schools--a testament to his impact.

But Bennett, a devout Catholic, has always been more Old Testament than New. Even many who sympathize with his concerns find his combative style haughty and unforgiving. Democrats in particular object to his partisan sermonizing, which portrays liberals as inherently less moral than conservatives, more given to excusing personal weaknesses, and unwilling to confront the vices that destroy families. During the impeachment of Bill Clinton, Bennett was among the president's most unrelenting detractors. His book, The Death of Outrage, decried, among other things, the public's failure to take Clinton's sins more seriously.

His relentless effort to push Americans to do good has enabled Bennett to do extremely well. His best-selling The Book of Virtues spawned an entire cottage industry, from children's books to merchandizing tie-ins to a PBS cartoon series. Bennett commands $50,000 per appearance on the lecture circuit and has received hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants from such conservative benefactors as the Scaife and John M. Olin foundations.

Few vices have escaped Bennett's withering scorn. He has opined on everything from drinking to "homosexual unions" to "The Ricki Lake Show" to wife-swapping. There is one, however, that has largely escaped Bennett's wrath: gambling. This is a notable omission, since on this issue morality and public policy are deeply intertwined. During Bennett's years as a public figure, casinos, once restricted to Nevada and New Jersey, have expanded to 28 states, and the number continues to grow. In Maryland, where Bennett lives, the newly elected Republican governor Robert Ehrlich is trying to introduce slot machines to fill revenue shortfalls. As gambling spreads, so do its associated problems. Heavy gambling, like drug use, can lead to divorce, domestic violence, child abuse, and bankruptcy. According to a 1998 study commissioned by the National Gambling Impact Study Commission, residents within 50 miles of a casino are twice as likely to be classified as "problem" or "pathological" gamblers than those who live further away.

If Bennett hasn't spoken out more forcefully on an issue that would seem tailor-made for him, perhaps it's because he is himself a heavy gambler. Indeed, in recent weeks word has circulated among Washington conservatives that his wagering could be a real problem. They have reason for concern. The Washington Monthly and Newsweek have learned that over the last decade Bennett has made dozens of trips to casinos in Atlantic City and Las Vegas, where he is a "preferred customer" at several of them, and sources and documents provided to The Washington Monthly put his total losses at more than $8 million.

"I don't play the 'milk money.'"

Bennett has been a high-roller since at least the early 1990s. A review of one 18-month stretch of gambling showed him visiting casinos, often for two or three days at a time (and enjoying a line of credit of at least $200,000 at several of them). Bennett likes to be discreet. "He'll usually call a host and let us know when he's coming," says one source. "We can limo him in. He prefers the high-limit room, where he's less likely to be seen and where he can play the $500-a-pull slots. He usually plays very late at night or early in the morning--usually between midnight and 6 a.m." The documents show that in one two-month period, Bennett wired more than $1.4 million to cover losses. His desire for privacy is evident in his customer profile at one casino, which lists as his residence the address for Empower.org (the Web site of Empower America, the non-profit group Bennett co-chairs). Typed across the form are the words: "NO CONTACT AT RES OR BIZ!!!"

Bennett's gambling has not totally escaped public notice. In 1998, The Washington Times reported in a light-hearted front-page feature story that he plays low-stakes poker with a group of prominent conservatives, including Robert Bork, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, and Chief Justice William Rehnquist. A year later, the same paper reported that Bennett had been spotted at the new Mirage Resorts Bellagio casino in Las Vegas, where he was reputed to have won a $200,000 jackpot. Bennett admitted to the Times that he had visited the casino, but denied winning $200,000. Documents show that, in fact, he won a $25,000 jackpot on that visit--but left the casino down $625,000.

Bennett--who gambled throughout Clinton's impeachment--has continued this pattern in subsequent years. On July 12 of last year, for instance, Bennett lost $340,000 at Caesar's Boardwalk Regency in Atlantic City. And just three weeks ago, on March 29 and 30*, he lost more than $500,000 at the Bellagio in Las Vegas. "There's a term in the trade for this kind of gambler," says a casino source who has witnessed Bennett at the high-limit slots in the wee hours. "We call them losers."

Asked by Newsweek columnist and Washington Monthly contributing editor Jonathan Alter to comment on the reports, Bennett admitted that he gambles but not that he has ended up behind. "I play fairly high stakes. I adhere to the law. I don't play the 'milk money.' I don't put my family at risk, and I don't owe anyone anything." The documents offer no reason to contradict Bennett on these points. Bennett claims he's beaten the odds: "Over 10 years, I'd say I've come out pretty close to even."

"You can roll up and down a lot in one day, as we have on many occasions," Bennett explains. "You may cycle several hundred thousand dollars in an evening and net out only a few thousand."

"I've made a lot of money [in book sales, speaking fees and other business ventures] and I've won a lot of money," adds Bennett. "When I win, I usually give at least a chunk of it away [to charity]. I report everything to the IRS."

But the documents show only a few occasions when he turns in chips worth $30,000 or $40,000 at the end of an evening. Most of the time, he draws down his line of credit, often substantially. A casino source, hearing of Bennett's claim to breaking even on slots over 10 years, just laughed.

"You don't see what I walk away with," Bennett says. "They [casinos] don't want you to see it."

Explaining his approach, Bennett says: "I've been a 'machine person' [slot machines and video poker]. When I go to the tables, people talk--and they want to talk about politics. I don't want that. I do this for three hours to relax." He says he was in Las Vegas in April for dinner with the former governor of Nevada and gambled while he was there.

Bennett says he has made no secret of his gambling. "I've gambled all my life and it's never been a moral issue with me. I liked church bingo when I was growing up. I've been a poker player."

But while Bennett's poker playing and occasional Vegas jaunt are known to some Washington conservatives, his high-stakes habit comes as a surprise to many friends. "We knew he went out there [to Las Vegas] sometimes, but at that level? Wow!" said one longtime associate of Bennett.

Despite his personal appetites, Bennett and his organization, Empower America, oppose the extension of casino gambling in the states. In a recent editorial, his Empower America co-chair Jack Kemp inveighed against lawmakers who "pollute our society with a slot machine on every corner." The group recently published an Index of Leading Cultural Indicators, with an introduction written by Bennett, that reports 5.5 million American adults as "problem" or "pathological" gamblers. Bennett says he is neither because his habit does not disrupt his family life.

When reminded of studies that link heavy gambling to divorce, bankruptcy, domestic abuse, and other family problems he has widely decried, Bennett compared the situation to alcohol.

"I view it as drinking," Bennett says. "If you can't handle it, don't do it."

Bennett is a wealthy man and may be able to handle losses of hundreds of thousands of dollars per year. Of course, as the nation's leading spokesman on virtue and personal responsibility, Bennett's gambling complicates his public role. Moreover, it has already exacted a cost. Like him or hate him, William Bennett is one of the few public figures with a proven ability to influence public policy by speaking out. By furtively indulging in a costly vice that destroys millions of lives and families across the nation, Bennett has profoundly undermined the credibility of his word on this moral issue.

Reporting assistance provided by Robert W. J. Fisk, Soyoung Ho, and Brent Kendall.

A blog for lovers of the printed word (novels, short stories, poems--the Ing so to speak), popular film, politics, and casinos (the Bling).

Sunday, October 19, 2008

Virginia Beach Man Wins Lottery for the Third Time

Oh to be so lucky!

Thanks,

Preston

___________________________________

From Pilotonline.com

VIRGINIA BEACH

Luckiest. Guy. Ever.

It's not an official title, but it will do for Ralph Stephens.

The Virginia Beach man recently won the Virginia Lottery's Cash 5 drawing for the third time. Each time he matched all five numbers and walked away with the $100,000 top prize.

"It's amazing," said lottery spokesman John Hagerty. Hagerty did not know if the trifecta was unprecedented in Virginia Lottery history.

Stephens, who declined to be interviewed, picked up his first jackpot in 1997. Then, in April 2007, he again matched all five numbers and won another $100,000. And now, 16 months later, he's done it again.

Other contenders for luckiest people on Earth include a Chesapeake man who played the same numbers on 20 Cash 5 cards in 2004, raking in $1.8 million, and a Henrico County couple who won $9.7 million in 1991 and then $1,000 a week for life in 2002.

Thanks,

Preston

___________________________________

From Pilotonline.com

VIRGINIA BEACH

Luckiest. Guy. Ever.

It's not an official title, but it will do for Ralph Stephens.

The Virginia Beach man recently won the Virginia Lottery's Cash 5 drawing for the third time. Each time he matched all five numbers and walked away with the $100,000 top prize.

"It's amazing," said lottery spokesman John Hagerty. Hagerty did not know if the trifecta was unprecedented in Virginia Lottery history.

Stephens, who declined to be interviewed, picked up his first jackpot in 1997. Then, in April 2007, he again matched all five numbers and won another $100,000. And now, 16 months later, he's done it again.

Other contenders for luckiest people on Earth include a Chesapeake man who played the same numbers on 20 Cash 5 cards in 2004, raking in $1.8 million, and a Henrico County couple who won $9.7 million in 1991 and then $1,000 a week for life in 2002.

Labels:

crime,

gambler,

gamblers anonymous,

gambling,

luck,

quitting gambling

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Lipshitz 6

Reading T Cooper for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Lipshitz 6

Punk Blood

Jay Marvin

Click Here to Purchase Punk Blood

Breath, Eyes, Memory

Anonymous Rex

Reading Eric Garcia for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Anonymous Rex

Vinegar Hill

Reading A. Manette Ansay for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Vinegar Hill

Nicotine Dreams

Reading Katie Cunningham for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Nicotine Dreams

Junot Diaz

Pulitzer Prize Winner!!!

Click Here to Purchase The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Edwige Danticat

New Year's Reading

Click Here to Purchase Brother I"m Dying

Greed

This Brother Is Scary Good

Sweet Music

One More Chance

The genius Is At It Again/The Rapper CHIEF aka Sherwin Allen

Sandrine's Letter

Check out Sandrine's Letter To Tomorrow. You will like it, I insist.

Sandrine's Link

Cool Sites

- Akashic Books

- All or Nothing (My Other Blog)

- Asili The Journal

- Best Gamblling News Site

- Black Star Review

- Book Remarks

- Booktour.com

- Carolina Wren Press

- Click Here for Some Pretty Good Writing Contests

- Dedra Johnson

- Enrico Theoc

- Felicia Luna Lemus

- Florida Book Review

- Foreword Magazine

- Gambling Is Linked to Suicide

- Gambling Is Not Linked to Suicide

- Gaming Law Review

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Geoffrey Philp's Blog

- Get Chief's CDs on CD Baby

- Getting Past Gambling

- Gonzalo Barr's Blog

- Good Reads

- Hallema's Homepage

- Help With Gambling Addiction

- Jeremy Shipp's Website

- John Dufresne's Blog

- Leonard Nash Homepage

- Links to Seminole Casinos in Florida

- Martha Frankel's Homepage

- Michael A. Gonzales

- Miss Snark/ An Agent Gives Great Publishing Advice

- More Addiction Help

- No Gambling.com

- Pat MacEnulty

- ScrewIowa.com

- St. Louis Rams, The Greatest Show on Turf

- Suicide reference library

- T Cooper

- University of Florida

- Vicki Hendricks

- Walter Jacobs's Blog

- Writers Who Read

- Writing with Celia

All or Nothing

Editorial Reviews of All or Nothing

New York Times--". . . a cartographer of autodegradation . . . Like Dostoyevsky, Allen colorfully evokes the gambling milieu — the chained (mis)fortunes of the players, their vanities and grotesqueries, their quasi-philosophical ruminations on chance. Like Burroughs, he is a dispassionate chronicler of the addict’s daily ritual, neither glorifying nor vilifying the matter at hand."

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

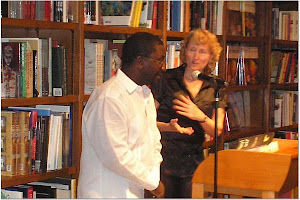

At Books and Books

Me And Vicki at Our Reading

Bio

Preston L. Allen is the recipient of a State of Florida Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature and the Sonja H. Stone Prize in Fiction for his short story collection Churchboys and Other Sinners (Carolina Wren Press 2003). His works have appeared in numerous publications including The Seattle Review, The Crab Orchard Review, Asili, Drum Voices, and Gulfstream Magazine; and he has been anthologized in Here We Are: An Anthology of South Florida Writers, Brown Sugar: A Collection of Erotic Black Fiction, Miami Noir, and the forthcoming Las Vegas Noir. His fourth novel, All Or Nothing, chronicles the life of a small-time gambler who finally hits it big. Preston Allen teaches English and Creative Writing in Miami, Florida.