To paraphrase Stephen King in his book On Writing, “Writers do their jobs and editors do theirs. Trust your editor.”

The first time I worked with an editor, it was with a short story, and I got back this message: “I just love the story! There are hardly any edits to make at all. I’ll just give you a call and we’ll discuss the few changes that need to be made.”

“Cool,” I said.

Then the next day I got another message: “You know what? Maybe it’ll be easier if I jot the few marks on the manuscript and send it back to you, then you look over it and get back to me.”

“Cool,” I said.

When I got the manuscript in the mail, there were like seventeen pages of corrections on a twenty-page story—red marks were everywhere. I got depressed.

My writer’s tender ego bruised, I put the thing down and surrendered to dark thoughts for about three weeks—three weeks later the editor sent a message: “I haven’t heard from you. Are you okay? Have you looked over my edits?”

“You hate the story,” I said.

She said, “What? I’m crazy about the story.”

I said, “But there are like red marks all over it. There are suggestions to make major changes. I thought you said you like the story and that there was nothing wrong with it.”

She said, “I’m an editor. It’s my job to make your writing say what you think you made it say.”

Oh.

You see, the problem with me was that before working with this editor I had published many fine stories in many fine magazines without anyone else’s help and/or interference. For me, as with most authors, writing was a solitary exercise.

Oh sure, back during the MFA phase, we workshopped each other’s stories, but for the most part, the only editor that we truly trusted was the one living in our heads.

Every perfectly chosen word, every profound nuance of sentence structure, every brilliant image that we set down on the page was created and approved by us. This is what made us brilliant geniuses. This is what set us apart from the mere mortals of this world. We needed help from no one.

Thus we deservedly hogged all the glory when the finished project was presented to the world and praised for its exemplary use of such and such and its amazing, dazzling displays of so and so. We feared that an editor would make so many changes that they would in some ways “steal” our story and make it their own.

But if you are going to receive pay for your writing, you had better learn to work with someone who is skilled at making sure that you say what you think you are saying.

Publishing houses are not concerned with whether you think you are brilliant or not. They are interested in selling books. The editor is their professional, and he/she represents their will.

Remember that it is your story—but it is their book.

Their cover. Their binding. Their isbn number. Their paper upon which it is printed. Their factory and warehouse for making and storing the thing. Their advertising. Their connections with bookstores to get it on the shelves. Their editor. And your story idea—which their editor will help you to “fix” so that it fits their cover, their binding, their advertising—you get the picture.

Oh, and by the way, who gets all the praise when it’s all put together successfully? You, the author. Cool.

A little story I’ve heard: D.H. Lawrence was notorious for turning in unfinished and incomplete manuscripts. His editor, who admired him, would often complete the books for him. What is the name of that editor? Who knows? Go look it up. Not that it matters—you won’t have heard of him anyway. It’s D.H. Lawrence who is the great writer of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the “Rocking Horse Winner.”

I have been fortunate to have worked with some pretty dang good editors—Carol Taylor, Andrea Selch, Ellen Milmed, Katie Blount, Jarret Keene, among them. They did not “steal” my story and make it their own, as so many writers fear an editor will do.

Instead, I found myself saying at so many points during the process of their editing, “Yes. Yes, that is exactly what I was trying to say,” or, “I would have caught that given more time and that is exactly the change I would have made,” or, “I did not see it like that before, no, no, but it makes so much sense that way, and it is consistent with things I’ve written elsewhere in the book. Gee, I’m glad you caught that,” or “Yes, yes, you’re right. I was just showing off there. We can cut that part.”

What my editors did, because they are good editors, is to reduce the unnecessary layer of clumsy, grasping, distracting egoism that I and so many writers color their writing with and excuse it by calling it style or personality.

In other words, editors reduce the “noise” of the writer’s own annoying habits (which he/she calls style. Style my butt!). Editors make your story cleaner.

Now there do exist a few bad editors, I am sure, but I will let someone else’s blog deal with that breed. But we needn’t worry too much about them if we rest our faith in two absolute truths:

(A) Editors won’t exist long in this business if they are bad; and (B) the writer’s typically large and overblown ego, which is shield enough, unfortunately, to defend the manuscript against a good editor, is certainly more than a match for a bad editor.

A blog for lovers of the printed word (novels, short stories, poems--the Ing so to speak), popular film, politics, and casinos (the Bling).

Saturday, December 8, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Lipshitz 6

Reading T Cooper for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Lipshitz 6

Punk Blood

Jay Marvin

Click Here to Purchase Punk Blood

Breath, Eyes, Memory

Anonymous Rex

Reading Eric Garcia for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Anonymous Rex

Vinegar Hill

Reading A. Manette Ansay for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Vinegar Hill

Nicotine Dreams

Reading Katie Cunningham for Christmas

Click Here to Purchase Nicotine Dreams

Junot Diaz

Pulitzer Prize Winner!!!

Click Here to Purchase The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Edwige Danticat

New Year's Reading

Click Here to Purchase Brother I"m Dying

Greed

This Brother Is Scary Good

Sweet Music

One More Chance

The genius Is At It Again/The Rapper CHIEF aka Sherwin Allen

Sandrine's Letter

Check out Sandrine's Letter To Tomorrow. You will like it, I insist.

Sandrine's Link

Cool Sites

- Akashic Books

- All or Nothing (My Other Blog)

- Asili The Journal

- Best Gamblling News Site

- Black Star Review

- Book Remarks

- Booktour.com

- Carolina Wren Press

- Click Here for Some Pretty Good Writing Contests

- Dedra Johnson

- Enrico Theoc

- Felicia Luna Lemus

- Florida Book Review

- Foreword Magazine

- Gambling Is Linked to Suicide

- Gambling Is Not Linked to Suicide

- Gaming Law Review

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Gene Durnell's The Thinking Journalist

- Geoffrey Philp's Blog

- Get Chief's CDs on CD Baby

- Getting Past Gambling

- Gonzalo Barr's Blog

- Good Reads

- Hallema's Homepage

- Help With Gambling Addiction

- Jeremy Shipp's Website

- John Dufresne's Blog

- Leonard Nash Homepage

- Links to Seminole Casinos in Florida

- Martha Frankel's Homepage

- Michael A. Gonzales

- Miss Snark/ An Agent Gives Great Publishing Advice

- More Addiction Help

- No Gambling.com

- Pat MacEnulty

- ScrewIowa.com

- St. Louis Rams, The Greatest Show on Turf

- Suicide reference library

- T Cooper

- University of Florida

- Vicki Hendricks

- Walter Jacobs's Blog

- Writers Who Read

- Writing with Celia

All or Nothing

Editorial Reviews of All or Nothing

New York Times--". . . a cartographer of autodegradation . . . Like Dostoyevsky, Allen colorfully evokes the gambling milieu — the chained (mis)fortunes of the players, their vanities and grotesqueries, their quasi-philosophical ruminations on chance. Like Burroughs, he is a dispassionate chronicler of the addict’s daily ritual, neither glorifying nor vilifying the matter at hand."

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

Florida Book Review--". . . Allen examines the flaming abyss compulsive gambling burns in its victims’ guts, self-esteem and bank accounts, the desperate, myopic immediacy it incites, the self-destructive need it feeds on, the families and relationships it destroys. For with gamblers, it really is all or nothing. Usually nothing. Take it from a reviewer who’s been there. Allen is right on the money here."

Foreword Magazine--"Not shame, not assault, not even murder is enough reason to stop. Allen’s second novel, All or Nothing, is funny, relentless, haunting, and highly readable. P’s inner dialogues illuminate the grubby tragedy of addiction, and his actions speak for the train wreck that is gambling."

Library Journal--"Told without preaching or moralizing, the facts of P's life express volumes on the destructive power of gambling. This is strongly recommended and deserves a wide audience; an excellent choice for book discussion groups."—Lisa Rohrbaugh, East Palestine Memorial P.L., OH

LEXIS-NEXIS--"By day, P drives a school bus in Miami. But his vocation? He's a gambler who craves every opportunity to steal a few hours to play the numbers, the lottery, at the Indian casinos. Allen has a narrative voice as compelling as feeding the slots is to P." Betsy Willeford is a Miami-based freelance book reviewer. November 4, 2007

Publisher’s Weekly--"Allen’s dark and insightful novel depicts narrator P’s sobering descent into his gambling addiction . . . The well-written novel takes the reader on a chaotic ride as P chases, finds and loses fast, easy money. Allen (Churchboys and Other Sinners) reveals how addiction annihilates its victims and shows that winning isn’t always so different from losing."

Kirkus Review--"We gamble to gamble. We play to play. We don't play to win." Right there, P, desperado narrator of this crash-'n'-burn novella, sums up the madness. A black man in Miami, P has graduated from youthful nonchalance (a '79 Buick Electra 225) to married-with-a-kid pseudo-stability, driving a school bus in the shadow of the Biltmore. He lives large enough to afford two wide-screen TVs, but the wife wants more. Or so he rationalizes, as he hits the open-all-night Indian casinos, "controlling" his jones with a daily ATM maximum of $1,000. Low enough to rob the family piggy bank for slot-machine fodder, he sinks yet further, praying that his allergic 11-year-old eat forbidden strawberries—which will send him into a coma, from which he'll emerge with the winning formula for Cash 3 (the kid's supposedly psychic when he's sick). All street smarts and inside skinny, the book gives readers a contact high that zooms to full rush when P scores $160,000 on one lucky machine ("God is the God of Ping-ping," he exults, as the coins flood out). The loot's enough to make the small-timer turn pro, as he heads, flush, to Vegas to cash in. But in Sin City, karmic payback awaits. Swanky hookers, underworld "professors" deeply schooled in sure-fire systems to beat the house, manic trips to the CashMyCheck store for funds to fuel the ferocious need—Allen's brilliant at conveying the hothouse atmosphere of hell-bent gaming. Fun time in the Inferno.

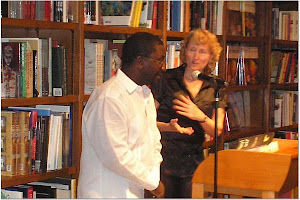

At Books and Books

Me And Vicki at Our Reading

Bio

Preston L. Allen is the recipient of a State of Florida Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature and the Sonja H. Stone Prize in Fiction for his short story collection Churchboys and Other Sinners (Carolina Wren Press 2003). His works have appeared in numerous publications including The Seattle Review, The Crab Orchard Review, Asili, Drum Voices, and Gulfstream Magazine; and he has been anthologized in Here We Are: An Anthology of South Florida Writers, Brown Sugar: A Collection of Erotic Black Fiction, Miami Noir, and the forthcoming Las Vegas Noir. His fourth novel, All Or Nothing, chronicles the life of a small-time gambler who finally hits it big. Preston Allen teaches English and Creative Writing in Miami, Florida.

No comments:

Post a Comment